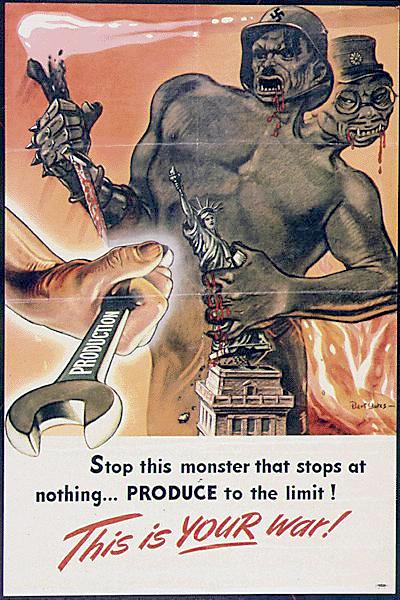

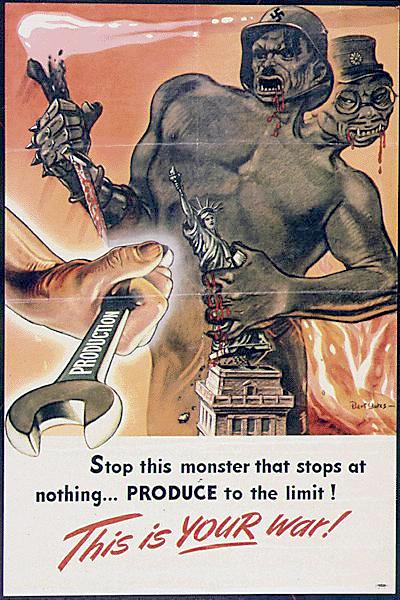

We soon learned about our enemies. The message was unmistakably clear.

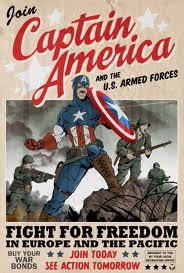

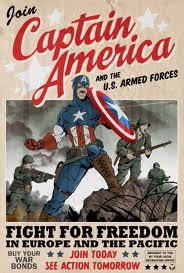

And we knew who we were.

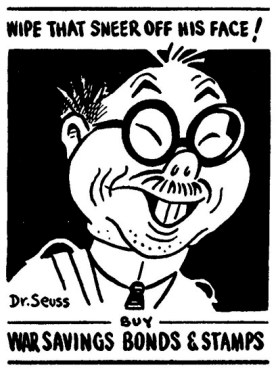

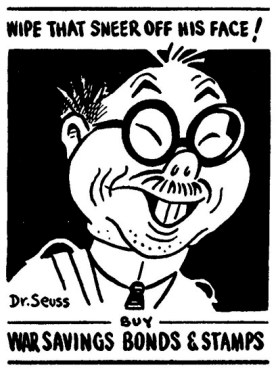

Even Dr. Seuss stood on the side of right.

The fall of 1940. A momentous year. Kindergarten.

We lived on 11th Avenue in Oakland. Bella Vista Grammar School stood a block up the hill and across the intersection. Miss Wallman the teacher.

The first day turned out to be somewhat traumatic.

I had learned to read at a precocious age. I was far ahead of anyone else in the class. That fact proved to be irrelevant because I felt completely at one with everyone else. The furniture provided a bond.

We entered, that first day, to find ourselves in a bright, cheerful room. Pictures and letters and everything a kindergarten room should be. I noticed none of it. I only noticed the chairs and the tables. Wonder of wonders, they were small. My size. I’d never sat in a chair like that. My feet touched the ground. My elbows rested on the table. Lost in the tactile moment I ran my hands over the smooth wood of the sides of the seat.

The wonder of it continued to hold my attention. I barely noticed when  Miss Wallman told us that in the future we would be paired. Whenever we went anywhere each of us would walk with the same other child. I was paired a girl who had long brown hair. She sat across the table from me. She wore MaryJanes.

Miss Wallman told us that in the future we would be paired. Whenever we went anywhere each of us would walk with the same other child. I was paired a girl who had long brown hair. She sat across the table from me. She wore MaryJanes.

We were told to tell each other our names. Her name was Elizabeth. “E * liz * a * beth” she sounded out.

For some unknown reason I couldn’t pronounce it. Try as I might it came out “E * lith * a * bus.”

I tried several times. It came out the same. Apparently out of sheer frustration she threw a crayon at me. It bounced off my shoulder. I scrambled down to get it and throw it back at her. At that moment we caught Miss Wallman’s attention. Or I did. Elizabeth sat primly in her chair.

Just as I stood up with the crayon, Miss Wallman arrived. Snatching me by the back of my collar, she yanked me upright. So tightly did she pull me up that my arms splayed wide. Probably my eyes bugged out as well.

The rest of the class, Elizabeth included, watched with a certain abstract interest to see what would happen to the miscreant wretch I had proven to be.

Swiftly the teacher dealt out summary justice. In tones stentorian she announced the form that capital punishment henceforth would take for anyone who pushed too far the boundaries of propriety—

The Thick Chair

I was now the poster child.

I never found out where the name came from. I thought maybe every kindergarten had one. The Thick Chair sat in the far corner of the room behind a folding screen. The seat was indeed thick. Hard.

When we got there the chair was so large I couldn’t get into it by myself. Miss Wallman had to help. There I sat. My feet dangled down, nowhere near the floor.

Inches away from my face stood the screen. I could see only the texture of the cloth.

I could listen only to the happy sounds of my classmates as they used blunt scissors to cut shapes out of paper.

I suffered in silence. After what seemed hours Miss Wallman liberated me. Now chastised I returned to my little chair and resumed my place in the class.

Elizabeth smiled at me.

In 1939 two important things happened. Uncle Ted helped Dad get a job where he worked at Colgate-Palmolive-Peets in Emeryville, just down from Berkeley. Mom and Dad had saved enough to buy a house. They bought one in Oakland. After that we’d often go back to visit Aunt Jerry and Uncle Ted in Pleasanton. When we did, I always hoped we’d stop for gas at the service station at the crossroads in Dublin.

The gas station filled me with wonder. We’d pull up to the pump. I’d scramble across the back seat, stand on it and watch with awe as the process went on. To see better Dad let me roll down the window. Getting out of the car, Dad would make the purchase. Gas cost nine cents a gallon.Sometimes he’d buy ten gallons. He’d hand the attendant a dollar. Ninety cents with a dime left over.

The gas station filled me with wonder. We’d pull up to the pump. I’d scramble across the back seat, stand on it and watch with awe as the process went on. To see better Dad let me roll down the window. Getting out of the car, Dad would make the purchase. Gas cost nine cents a gallon.Sometimes he’d buy ten gallons. He’d hand the attendant a dollar. Ninety cents with a dime left over.

Then the real magic would begin.

The attendant would go to one of two pumps, one for regular and one for ethyl. Dad bought regular. A round glass cylinder made up the top of each pump. Inside it ran a metal scale that calibrated the gallons. I think it held up to twenty gallons. The size of the jar impressed me deeply. It seemed huge.

Once he knew how much Dad wanted to buy, the attendant would attach a marker to the outside of the pump.  Then he use a pump handle on the front of the pump to fill the jar. He had to pump vigorously to lift the ruby red gas into the glass cylinder. Up, up it would splash. Carefully he’d pause to make sure he’d reached the gallons Dad had bought. Dad watched carefully as well.

Then he use a pump handle on the front of the pump to fill the jar. He had to pump vigorously to lift the ruby red gas into the glass cylinder. Up, up it would splash. Carefully he’d pause to make sure he’d reached the gallons Dad had bought. Dad watched carefully as well.

Once the man had put the nozzle in the car’s gas tank, he’d push a switch. Gravity took over. Down flowed the gasoline through a white hose into the car. As the gas in the jar emptied, it did so with great burps and blorps of bubbles, silently splashing violently inside the glass. A sight to behold!

Once he’d finished came the best moment of all. The man would go back into the station and bring out a brown wicker basket filled with lollipops. Reaching out of the window, I’d take my pick. This was no ordinary sucker, mind you. Rather than a stick to hold onto it had a loop of rope. If I got tired of sucking the candy I could, with royal aplomb, standing behind Mom and Dad, leaning on the back of the seat, observing the road ahead, lick it.

Sometimes I made it last even after we got to the Aunt Jerry and Uncle Ted’s place in the fields north of Pleasanton.

I slept in the bedroom with my cousin. He was older. He went to school. He resented having to share his bedroom with me.

In those days, when insulation was an unknown, heat escaped mercilessly. The livingroom at the far end of the hall, the bedrooms and bathroom, the hall itself—all of them chilled overnight. Slowly the temperature dropped, even though summer still held.

In those days, when insulation was an unknown, heat escaped mercilessly. The livingroom at the far end of the hall, the bedrooms and bathroom, the hall itself—all of them chilled overnight. Slowly the temperature dropped, even though summer still held.

Getting up in the morning followed the same pattern. I’d wake up, usually with the covers over my head and only a small hole through which to breathe. When I pushed back the covers I could see my breath in the cold morning air. I only pushed them back after I heard Uncle Ted stomp on the back porch as he came in from milking the cow.

I’d get out of bed and go to the chair where I had laid out by pants the night before. As soon as my suspenders were properly on my shoulders I’d pick up shoes, sox and shirt, hurry through the door and down the hall. Opening the door to the kitchen I’d slip through. Blessed warmth surrounded me. I had a chair to one side of the stove where, in its warmth, I’d sit and finish dressing.

Warmth from Aunt Jerry’s stove filled the kitchen. Her stove dominated it. Polished chrome set off the white of the doors and the black of the stovetop. The stove burned coal.  Uncle Ted kept the lumps in a black metal bucket especially made for it. Uncle Ted regularly added coal to the firebox. He had to be careful. Aunt Jerry hated coal dust. As he added to the fire I’d stand behind him so I could look over his shoulder and see how fiercely it burned.

Uncle Ted kept the lumps in a black metal bucket especially made for it. Uncle Ted regularly added coal to the firebox. He had to be careful. Aunt Jerry hated coal dust. As he added to the fire I’d stand behind him so I could look over his shoulder and see how fiercely it burned.

Breakfast cereal was an unknown, something rich people ate. Not us. Sometimes Aunt Jerry made pancakes or biscuits. Toast was more often called for. On those days, I played my part in the ritual of breakfast. She would scour the black top over the firebox. I would take a piece of bread and place it carefully on the black. I was just tall enough to see where to put it.

Several moments would pass. Pinching the crust, I’d turn it over. Once toasted on the second side, I’d pick it up and put it on a plate Uncle Ted held out for me. He’d butter. I’d watch fascinated as the melting butter filled the little white dimple where my fingers had pinched the crust. Once buttered he ‘d put the plate in the warming oven above the stovetop.

Several moments would pass. Pinching the crust, I’d turn it over. Once toasted on the second side, I’d pick it up and put it on a plate Uncle Ted held out for me. He’d butter. I’d watch fascinated as the melting butter filled the little white dimple where my fingers had pinched the crust. Once buttered he ‘d put the plate in the warming oven above the stovetop.

After breakfast Aunt Jerry would make sandwiches for my cousins. I’d stand next to her leaning against the counter, feeling the cold from the stone soak into my cheek. Her deft hands spoke of care and order.

In my mind she and her stove remained inseparably bound together.

In the years before World War II, Mom and Dad were migrant workers. Summers they worked in the lettuce sheds in Salinas, Mom trimming and Dad packing. In winter they’d go to Arizona, somewhere near Yuma I think, to work the melons.

I spent much of my first years with my Aunt and Uncle near Pleasanton. Aunt Jerry and Uncle Ted.

Selling milk in those years was serious business. Even though Uncle Ted had a regular job,  morning and night he still milked Mom Babe, their cantankerous Jersey cow. He would bring the milk into the house and strain it through folded layers of cheesecloth into a shiny five gallon metal container. The container had a metal top attached to it by a small chain. At a precisely timed moment, he would take the can out to the end of the driveway. Almost immediately the truck from the creamery in Pleasanton would pull up, collect the container and, having left off a clean empty, proceed down the road to the next driveway.

morning and night he still milked Mom Babe, their cantankerous Jersey cow. He would bring the milk into the house and strain it through folded layers of cheesecloth into a shiny five gallon metal container. The container had a metal top attached to it by a small chain. At a precisely timed moment, he would take the can out to the end of the driveway. Almost immediately the truck from the creamery in Pleasanton would pull up, collect the container and, having left off a clean empty, proceed down the road to the next driveway.

This regimen he followed, morning and night. I’m sure Uncle Ted would have preferred to milk later in the evening when the cool had arrived. Given the inflexible pickup schedule, he had no choice. He would come home from his day job, change clothes and go directly out to the shed.

This regimen he followed, morning and night. I’m sure Uncle Ted would have preferred to milk later in the evening when the cool had arrived. Given the inflexible pickup schedule, he had no choice. He would come home from his day job, change clothes and go directly out to the shed.

In the late afternoon I’d go with him, clutching my little enameled tin cup in one hand and holding one of his fingers in the other. I had to run on my stubby legs to keep up with him. Once in the shed I’d climb up the side of the partition next to the stanchion. I’d wait there, hanging with my elbows on the top, while he brought Babe in, put her in the stanchion, dropped a full can of mash in the trough and then got on with the business of milking. The cats accompanied us.

Uncle Ted sat on a one-legged stool. Once he had cleaned her bag and she’d let her milk down, he milked in earnest, pulling first one tit and then the next in rhythmic order, working industriously to fill the five-gallon bucket. I listen impatiently to the milk hiss into the bucket. At some point early on he’d pause, reach back for my cup and milk it full. Wonderful taste, milk warm from the cow. The foam would stick to my upper lip.

Once he’d filled my cup Uncle Ted would take the right front tit in hand, lean back and  shoot a stream across to each cat. Up on their hind legs they would stand in turn, mouths open wide. Uncle never missed. Right in the kisser, one full pull on the tit. Satisfied, each cat would sit back and proceed to clean the milk splatter from the fur.

shoot a stream across to each cat. Up on their hind legs they would stand in turn, mouths open wide. Uncle never missed. Right in the kisser, one full pull on the tit. Satisfied, each cat would sit back and proceed to clean the milk splatter from the fur.

As he milked a strange process regularly began. I did not understand it. I only observed. Babe would, of course, regularly swish her tail to get rid of flies. But once she had eaten most of the mash Uncle had given her, she would swish it up onto her back, leave it there for a moment and then gently let it slide off to plop down and rest on his shoulders. This became  especially bothersome on the hot summer days when he would have taken off his shirt. Regularly I’d hear him muttering to himself.

especially bothersome on the hot summer days when he would have taken off his shirt. Regularly I’d hear him muttering to himself.

He’d shrug off the tail.

She’d again deposit it on his shoulders.

Again he’d shrug it off.

One hot summer afternoon he evidently reached something of a breaking point. Along with  the milk bucket he brought with him to the barn a heavy brick and a length of baling wire. He closed Babe in the stanchion. He put mash in the trough. Then he wrapped the wire securely around the brick and then around the end of her tail.

the milk bucket he brought with him to the barn a heavy brick and a length of baling wire. He closed Babe in the stanchion. He put mash in the trough. Then he wrapped the wire securely around the brick and then around the end of her tail.

At first she did not seem to notice. Her initial concern, as always, was the mash. That evening while she ate she tried, several times, to swish her tail. The brick held it down. At last, as if ready to get serious about things, she began to swish her tail in earnest. Back and forth it went, gradually increasing its arc. Like a pendulum in the grandfather clock in the house, back and forth it swept.

Uncle Ted was of course oblivious to this. Milking was serious business. His bald head pushed firmly against her flank, he concentrated on filling the bucket. Then, as fate would have it, he sat up, leaned back and looked to his left. At precisely that moment the brick reached a kind of critical mass. Around it came, slowly tracing a graceful arc. As if predestined, with a thud it met his forehead.

Back he fell. Startled, Babe stepped forward, kicking over the bucket. White milk splashed over the straw and manure. The cats squalled in terror. Babe lowed. I hung tight on the railing.

Lying there in the straw, Uncle Ted, in a loud voice, talked to the cow. Being only four I did not understand much of what he said. I only knew these were words I had been told I must never use.

Crawling around on his hands and knees, Uncle got hold of the brick. He stripped it off her tail. Babe mooed and kicked.

He let her out of the stanchion.

She ran from the shed.

He returned to the house. Aunt Jerry bandaged his head.