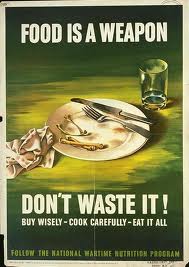

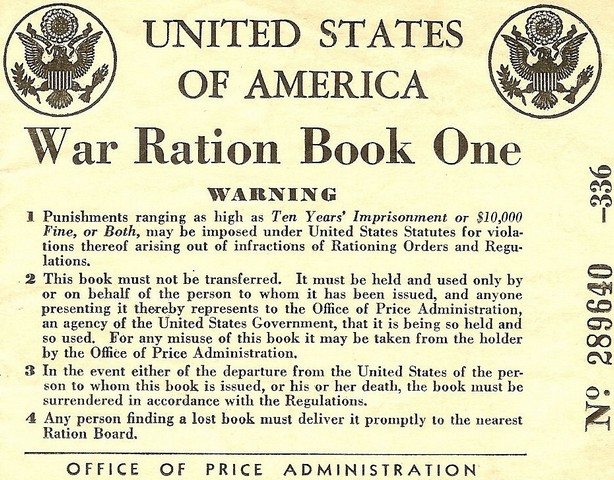

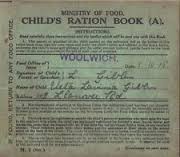

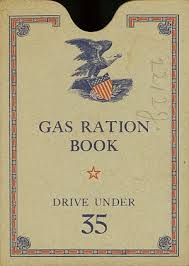

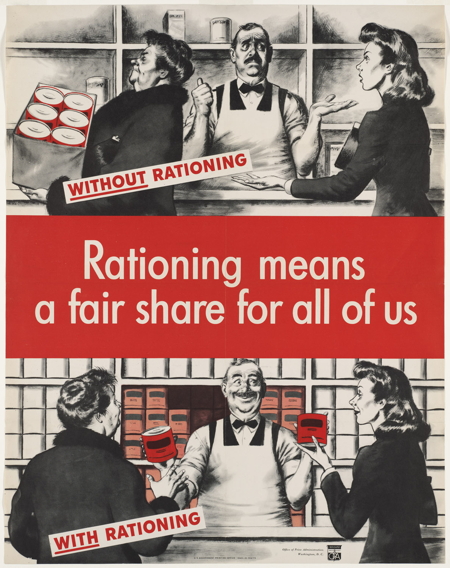

Over time a complicated family economy came into being. It didn’t really “develop.” More than anything it simply seemed to happen. It began with the chickens. As soon as they were big enough, we began to eat the roosters. We had fried chicken at last twice a week. The eggs  were another matter. As rationing continued, eggs became a prime source of barter. Dad would trade them for stamps. Most often gas stamps. Everyone won. Those on the other hand got eggs without monetary cost. We got stamps, the way to freedom.

were another matter. As rationing continued, eggs became a prime source of barter. Dad would trade them for stamps. Most often gas stamps. Everyone won. Those on the other hand got eggs without monetary cost. We got stamps, the way to freedom.

For Mom and Dad, freedom to recreate meant a couple of things. Often on Saturday or Sunday the extended family would gather, usually at Aunt Jerry and Uncle Ted’s, for dinner. While I looked forward to that, the barter system gave us something at once subtle and pervasive: movement.

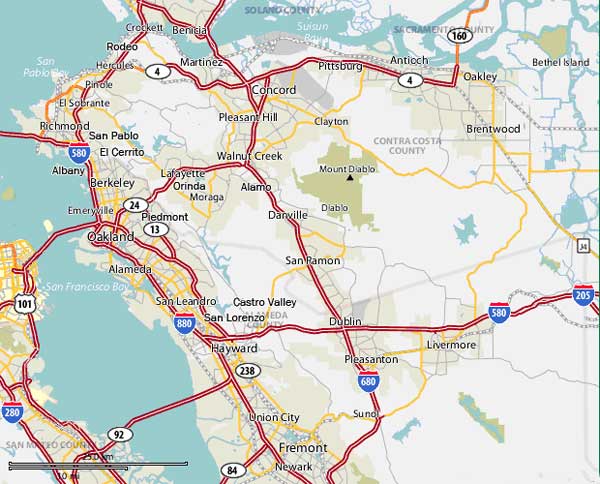

Extra gas stamps meant we could indulge in our prime recreation: going for a ride. Often Dad would marshal us into the car. I would stand behind the front seat. Mom held Bill while Dad drove. A complex system of roads radiated out from Walnut Creek. They’d pick  one or another and we’d drive along, noticing this and remarking on that as we went. What had happened to this place or that–who had painted a house, built a garage, fenced a chicken yard, planted a garden, harvested vegetables. On and on. A litany of minutia to be noted and repeated and commented upon and digested. Sometimes we’d stop at a roadside stand and buy corn or beans or melons.

one or another and we’d drive along, noticing this and remarking on that as we went. What had happened to this place or that–who had painted a house, built a garage, fenced a chicken yard, planted a garden, harvested vegetables. On and on. A litany of minutia to be noted and repeated and commented upon and digested. Sometimes we’d stop at a roadside stand and buy corn or beans or melons.

During childhood going for a drive seemed a normal and natural way to spend a weekend afternoon. Only much later did I realize for my parents it answered a deeper and more complex need. Mom and Dad grew up in the midwest, Mom in Oklahoma and Dad in Texas. Both of them were profoundly bound to place. As children they rarely ever left where they lived. Then came the migration to California. Out of the deprivation of the Dust Bowl to the green of the west. Movement.

For Dad and especially his brothers one image encapsulated it all: Alcatraz.

Most of Dad’s brothers and sisters settled in Salinas, a hundred or so miles south of Walnut Creek. Given the state of roads–as well as gas rationing–visits were a major event. Now  and again one of my Uncles would come to see us. Their cars were better than ours. One drove a Hudson. It had big windows. Invariably the visit would include Alcatraz. We’d load into the car, usually with Dad and his brother in the front with Bill between them. Mom and I along with various aunts and cousins sat in back

and again one of my Uncles would come to see us. Their cars were better than ours. One drove a Hudson. It had big windows. Invariably the visit would include Alcatraz. We’d load into the car, usually with Dad and his brother in the front with Bill between them. Mom and I along with various aunts and cousins sat in back

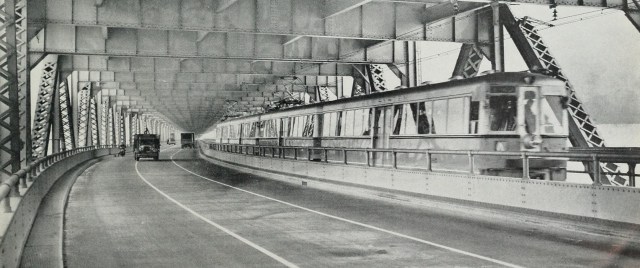

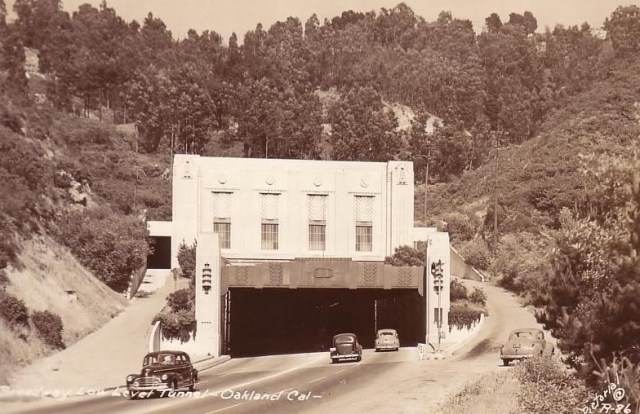

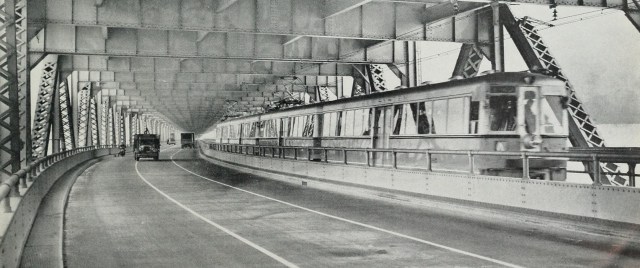

From Walnut Creek we’d go west. The thrill of  going through the tunnel. But this paled in comparison to crossing the Bay Bridge. When we drove on the lower level, sometimes an electric train would pass us.

going through the tunnel. But this paled in comparison to crossing the Bay Bridge. When we drove on the lower level, sometimes an electric train would pass us.

I’d stare down at Treasure Island. In 1940, before we moved from Oakland to Walnut  Creek, Mom and I had gone to the World’s Fair there. I remembered the crowds, and walking with Mom holding my hand. The buildings dwarfed me.

Creek, Mom and I had gone to the World’s Fair there. I remembered the crowds, and walking with Mom holding my hand. The buildings dwarfed me.

I remembered the huge statues of naked people.

I remembered the huge statues of naked people.

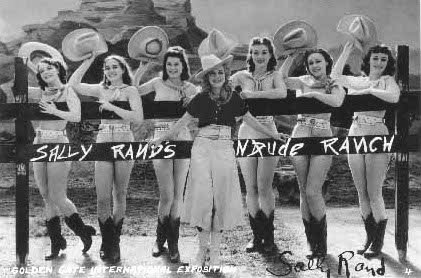

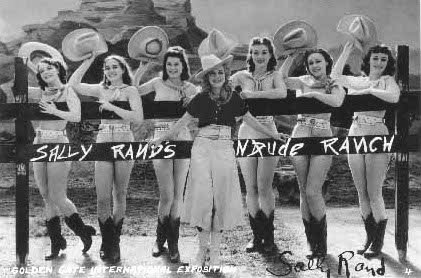

But most clearly I remembered Mom’s shocked tone of voice as later, when we got back home, she told Dad indignantly about the nude ladies.

A woman named Sally Rand had brought a show to the Worlds Fair. It featured women without clothes!

On we’d go to San Francisco. Down to the Embarcadero where huge ships were loaded with soldiers and with supplies for the war effort. Slowly Dad would drive along as we all stared out at the bay.

On we’d go to San Francisco. Down to the Embarcadero where huge ships were loaded with soldiers and with supplies for the war effort. Slowly Dad would drive along as we all stared out at the bay.

Then we’d find a place where we could see it. The supreme image of stasis. The prison where no one escaped. Alcatraz.

We’d park and look. No one got out of the car. For Dad and his brothers the image seemed to hold infinite fascination. They’d talk and talk about it. Still it did not seem to me they had much of anything to say. “Water sure looks cold.” “I’d hate to swim in it.” “Wonder how many prisoners there are.” “I’d sure hate to spend time there.” After they’d looked their fill, the car would start and we’d drive back home. No stopping at any of the restaurants. None of the other places we might visit. Back we’d drive to Walnut Creek.

Gas stamps meant mobility. Mobility in the larger family sense at times meant going to see the ultimate image of stasis, as if Alcatraz embodied, encapsulated the rootedness of the midwest childhood they had all escaped.